In Brief

How Myanmar Became a Global Center for Cyber Scams

Organized crime groups in Southeast Asia have seized on Myanmar’s instability amid civil war to establish a string of scam centers engaged in global online fraud operations.

Several Southeast Asian countries have become global hubs of cyber scamming, as organized crime groups have expanded their operations in the region amid Myanmar’s civil war and generally weak governance in surrounding countries, such as Cambodia. The crime networks are scamming hundreds of thousands of victims from countries in the region and beyond. While China and some Southeast Asian governments are attempting to crack down on the centers, the criminal operations could continue to evade law enforcement by hopping across the region.

What are these cyber scam centers?

Several well-connected organized criminal groups, mostly originating from China, are operating cyber scam centers across Southeast Asia, mainly in the poorer states of Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar. Their scams usually are efforts to con unwitting victims around the world out of their financial savings. Many of the organized crime groups came to these countries after Beijing began an anticorruption crackdown on illegal cross-border gambling and money laundering in Macau, a special administrative region of China located on its southern coast. (While casinos are illegal in mainland China, the ones just across the border from China, as well as in Macau, have long served as sources of profit, tools for money laundering, and bases of other illegal activities for organized crime groups.)

More on:

The centers are staffed by thousands of people, most of whom the criminal groups have illegally trafficked and forced to work in inhumane and abusive conditions. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights estimates that more than two hundred thousand people have been trafficked into Myanmar and Cambodia to execute these online scams. The trafficking networks reportedly stretch far beyond the region [PDF], pulling in victims from countries including Brazil, Kenya, and the Netherlands.

How do the scams work?

The trafficked workers typically contact their victims—most of whom reside in the United States or China—through text or online messaging apps and engage in elaborate attempts to develop close relationships with them and swindle them into fraudulent investments, such as phony cryptocurrencies. The scam is commonly known as “pig butchering”—which refers to fattening a pig before slaughter. A recent study found that between 2020 and 2024, victims worldwide lost approximately $75 billion to the Southeast Asian–based cyber scams. In the United States, Americans lost an estimated $2.6 billion in 2022 to pig butchering and other cryptocurrency fraud, according to the FBI.

Why are these scam centers proliferating in Myanmar?

Crime syndicates have flourished along Myanmar’s frontiers with China, India, Laos, and Thailand, areas that are dominated by an array of ethnic minority groups that have historically sought greater autonomy from the ruling Bamar, or Burman, majority. Tensions between the central government in Naypyidaw, the country’s capital, and the ethnic minorities’ armed organizations have flared following a military coup in 2021, which ousted the elected, quasi-democratic government.

Following the junta’s return to power, a variety of ethnic armed groups, many of which had been fighting the Myanmar military for decades, joined forces with new armed organizations primarily composed of ethnic Burmans. Together, they are attempting to topple the junta. Amid this power struggle, the scamming centers have thrived—as some ethnic armed groups and junta affiliates profit by informally taxing those illicit industries.

How has China responded to the scams within Myanmar?

The rise in Southeast Asian scam centers has altered China’s role in Myanmar’s civil war and its relationship with the military government, as many of the cyber scams and trafficking victims are Chinese citizens. Beijing has generally supported Myanmar’s junta to safeguard its Belt and Road infrastructure projects in the country and to prevent fighting or displacement from spilling into China’s Yunnan province. But the junta’s inability to crack down on scam centers, as well as the growing victimization of Chinese citizens, has changed China’s calculus.

More on:

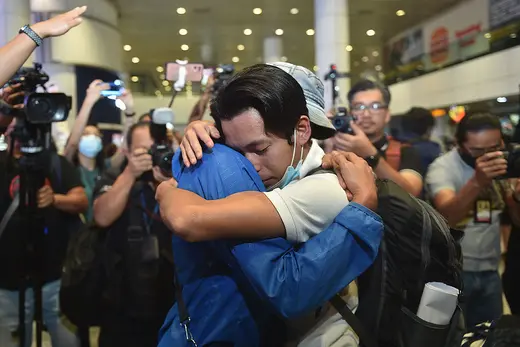

In late October 2023, three ethnic insurgent groups successfully coordinated an attack on the Myanmar military in northeastern Shan State. In their justification for launching the offensive, the ethnic armed groups claimed they would eliminate scam centers along the China-Myanmar border, accusing the junta of tolerating and profiting from the industry. Experts say China offered tacit approval for the attack, suggesting Beijing is willing to allow temporary instability on its border if it stops the human trafficking and scamming of its citizens. Chinese law enforcement is pressuring local ethnic militias to hand over Chinese nationals and close the scam centers. Since the counteroffensive, China has repatriated more than forty thousand citizens [link in Chinese], according to state-backed media.

What are other governments doing?

As China continues with its crackdown by repatriating scam kingpins and human trafficking victims, some criminal syndicates have shifted their enterprises to Myanmar’s eastern region of Karen State bordering Thailand. Thailand has accepted the military junta under previous governments, and crime syndicates have relied on access to electricity and telecommunications in Thailand to operate. However, some experts suggest that current Thai Prime Minister Sretta Thavisin has increasingly focused on the national security challenge that Myanmar’s scam centers pose to Thailand. In March 2024, Thailand assisted in a joint operation to repatriate almost one thousand citizens to China from Myanmar.

The United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom issued coordinated sanctions in December 2023 on individuals and entities involved with the scams, which followed previous sanctions issued shortly after the 2021 coup to cut off other revenue streams for the Myanmar military, such as the oil and gas industry. Meanwhile, U.S. authorities have taken action in some individual cases by seizing assets of those profiting from crypto scams. In one case, the Department of Justice seized $9 million worth of crypto, disrupting the financial infrastructure of the scam network.

In 2023, the U.S. Department of State released its latest Trafficking in Persons report, and its Burma (Myanmar) chapter documented cyber scam abuses in the country. Its findings serve as evidence for the United States to withhold non-humanitarian foreign aid from countries that are complicit in human trafficking—a tactic that the United States already implemented in Myanmar but not other neighboring countries complicit in human trafficking, such as Cambodia. Experts argue that cutting back U.S. assistance is one way Washington can address continued human trafficking.

What should policymakers expect next?

The future of scam operations in Myanmar is uncertain, particularly given the transnational nature of the problem and the uncertainty of the country’s civil war. Experts warn that these criminal enterprises are highly mobile and can easily elude a crackdown by dispersing their operations across borders. “Unfortunately, the law enforcement responses have been very much contained within national boundaries,” says Jason Tower, country director for Myanmar at the United States Institute of Peace.

Some experts say that as China continues its efforts to protect its own citizens from being scammed, the operations will likely seek even more victims in the West. Washington will need to ramp up its international collaboration, including raising this issue with China—as it has with its policy approach to fentanyl—to effectively protect U.S. citizens from these scams in the near future, Tower says.

Recommended Resources

The Center for Preventative Action tracks the civil war in Myanmar.

In this report by the United States Institute of Peace, experts dive into the global scale of cyber scam networks and provide policy recommendations to counter their malign effects.

This 2023 report by the U.S. Department of State outlines Myanmar’s failures in addressing human trafficking and provides policy recommendations.

In this original investigative report, Reuters journalists Poppy McPherson and Tom Wilson uncover millions of dollars tying the cyber scams with well-connected Chinese and Thai trade group representatives.

Will Merrow created the map for this article.

Online Store

Online Store